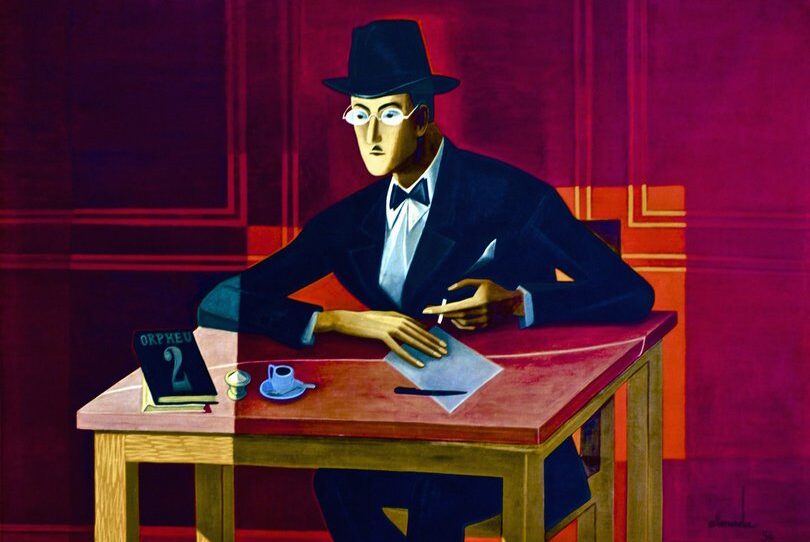

At the beginning of this year, I visited Lisbon for the first time, and thought I’d enhance the experience by reading some books set in Portugal’s capital. First, I read Nobel-laureate Jose Saramago’s The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, which is set in Lisbon in 1936 but whose titular protagonist is neither Saramago’s invention nor a historical figure. Ricardo Reis was one of several dozen “heteronyms” — literary alter-egos — dreamed up by Fernando Pessoa, the Lisboan writer who, little known when he died in 1935, is today celebrated as Portugal’s great modern poet (his tomb rests alongside those of Vasco de Gama and King Manuel I). The novel follows Reis through the final year of his life, during which he has a series of philosophically rich encounters… with the ghost of Fernando Pessoa.

On finishing the novel, I immediately started in on Pessoa: An Experimental Life by Richard Zenith. Admittedly, a 1,000-page tome about a spectacularly odd writer whose life, Zenith admits some 700 pages in, was “uneventful”, isn’t for everybody. And it confirmed my suspicion that Pessoa’s importance lies less in the quality of his writing than in the extraordinary novelty of his inner world. It seems ultimately fitting that Pessoa is interred next to de Gama, the first European to reach India by sea. Although in his 47 years on earth he rarely left his beloved Lisbon, he was an intrepid voyager of the inner cosmos, a discoverer of new worlds within the fathomless depths of the self. In the vast yet claustrophobic matrix of our online era, where identity is a febrile, paranoid play of masks and veils, his strange life story feels strikingly modern — and singularly poignant.

Pessoa is best known in the Anglophone world for his work of world-weary philosophical fragments and melancholy reveries, The Book of Disquiet, and for his unique mode of authorship. The aforementioned host of heteronyms each produced work in a distinctive style, and each bore a unique biography, character, ideological outlook, and even signature which Pessoa — like a child who never outgrew his imaginary friends — practised writing in his notebooks. Outwardly unassuming and diffident, Pessoa was a literary volcano that never stopped erupting — poems, essays, fictions, fragments, dialogues, and polemics spewed forth from his restless pen. But when it came to publishing, let alone self-publicising, he was hesitant to the point of self-effacement. In the final stretches of Pessoa: An Experimental Life, we find him still agonising over whether to publish a book at all (Mensagem, the only book of Portuguese poetry he published in his lifetime, appeared the year before his death).

He left behind a vast archive of work, much of it stored in his famous trunk, and much of it in varying states of incompletion. Pessoa was a champion unfinisher: project after project was started and then abandoned, or existed only on the many lists of future works he drew up for his gang of heteronyms to one day get round to. “None of it got written except for a brief opening paragraph,” reads a typical sentence in Zenith’s book. While some literary biographies dazzle with drama, Pessoa’s is remarkable for everything he didn’t do: have sex, publish much of anything, go anywhere. Norman Mailer he was not. Pessoa’s “experimental” life could no less accurately be called ineffectual — until you recall where his tomb now rests, and then it seems he wasn’t so ineffectual after all.

The key events in Fernando Pessoa’s life can be listed in a few lines. He was born into a comfortably bourgeois Lisbon family in 1888, which later relocated to Durban in South Africa. They returned to Portugal in 1905 after the better part of a decade and, for the rest of his life, Pessoa would never travel further from Lisbon than its nearby seaside resort towns Estoril and Cascais. As an adult he mostly made money writing business letters for various firms, and in a farcically inept venture, he established a printing and publishing press, Ibis, which quickly went out of business. He had a low-energy dalliance with a young woman named Ophelia, but eventually he spurned her affections. Almost certainly he was a closeted homosexual who died a virgin. Throughout his adulthood he hung out with fellow literati in Lisbon’s cafes, drank increasing volumes of wine and brandy, and wrote incessantly.

So much for the outward life. Uniquely, Pessoa: An Experimental Life begins with a “Dramatis Personae” of figures who existed only in its subject’s imagination. Pessoa distinguished his heteronyms from conventional pseudonyms: “Pseudonymous works are by the author in his own person, except in the name he signs; heteronymous works are by the author outside his own person. They proceed from a full-fledged individual created by him, like the lines spoken by a character in a drama he might write.” Pessoa had no wife or children and few close friends, but he dwelled in a clamorous psychic world of prolific literary companions who argued against, formed alliances, and otherwise engaged with one another. The three most important heteronyms were the Whitmanesque (and bisexual) Álvaro de Campos, the stately classicist Ricardo Reis, and Pessoa’s acknowledged “master”, Alberto Caeiro, who wrote serene bucolic verse and believed “that things are exactly what they seem to be”.

As Zenith quips in his prologue, “one could say that Portugal’s four greatest poets from the twentieth century were Fernando Pessoa”. Each was as fully imagined as the characters a novelist invents to populate his fictions, only the novel the heteronyms inhabited was the life of their author, Fernando Pessoa. And like a novelist dreaming up his characters, Pessoa experienced that strange necromancy of channelling voices that seemed to exist somehow beyond himself, that were more than their creator. Pessoa occasionally found himself writing better than he could write — achieving, through the schizoid ventriloquism of being possessed by his heteronyms, poetic effects that seemed to him beyond his own capacities. No stranger to mystical cosmologies, Pessoa toyed with the idea that his heteronyms were actually existing selves, conscious entities dwelling in a multitiered universe. At least to his own mind, Pessoa’s pursuit of writing unlocked hidden levels of the cosmic architecture. He was given to asking himself such deranging ontological questions as whether his alter-egos were his inventions, or he was theirs — whether he was nothing more nor less than “a series of dreams about me dreamed by someone outside me”.

Such cases of innovation in literary form facilitating metaphysical discovery are rare but not unheard of. In the mid-Seventies, a few decades after Pessoa’s death, the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick underwent a dramatic cosmic revelation (or psychotic breakdown, depending on one’s point of view) that prompted him to declare: “My novels and stories were, without my realising it consciously, autobiographical.” Dick spelled all this out to a dumbfounded science-fiction conference audience in France in a speech with the unbeatable title, “If You Find This World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others” (it reportedly took his listeners a while to realise Dick wasn’t merely detailing the plot of his latest novel). In the wake of his awed intimations of what today’s physicists tentatively call the multiverse, Dick became avidly interested in religious, esoteric and Gnostic thought, trying for the rest of his life to make sense of his shattering visionary experience.

Pessoa was likewise fascinated by such subjects as would come to preoccupy Dick. He wrote hundreds of poems and pages on esotericism and was fluent in the practices and theories of astrology, seances, Theosophy, Hermeticism, Kabbalah, secret societies, alchemy, and magic. Among the phases of literary influence he passed through was one spent in thrall to the Symbolist movement seeded by Charles Baudelaire, whose doctrine of “correspondences” — “whereby we who walk the world are said to pass through ‘forests of symbols’ that give us ‘knowing looks’” — was indebted to the mystical philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg. At the age of 42, Pessoa enjoyed a brief but mutually enriching friendship with the notorious magus and tabloid-favourite Aleister Crowley — a.k.a. the Great Beast 666 — after Pessoa wrote to him offering astrological advice and attaching some of his poems. (Their relationship fizzled out after Crowley visited Lisbon, recruited Pessoa to help him stage his own suicide, and then scarpered to Berlin.) Habitually staying up till the small hours drinking brandy and working on his texts, Pessoa wrote like a warlock-alchemist bent on transforming self and reality.

The cosmological conclusion Pessoa drew from his reading and writing was that there exist multiple levels of reality, and our grossly material, earthbound lives are but shadows of our true being on a higher, more brilliant plane. Although he took a keen interest in his nation’s political life, Pessoa became ever more hermetically devoted to the search for hidden mysteries and secret knowledge — gnosis. A letter he wrote to a young literary acquaintance in the final year of his life offers as clear a statement as any of Pessoa’s spiritual beliefs. In it, he professed his faith in “the existence of worlds higher than our own and in the existence of beings that inhabit those worlds”, and posited “various, increasingly subtle levels of spirituality that lead to a Supreme Being, who presumably created this world. There may be other, equally Supreme Beings who have created other universes that coexist with our own, separately or interconnectedly.” He suspected himself of being guided by higher forces, a mysterious Master or Masters hidden behind the veil of material reality: “Emissary of an unknown king, / I carry out hazy instructions from beyond.” When, like W.B. Yeats (to whom he also wrote letters), Pessoa began conducting experiments in automatic writing, one of the “spirits” who seized hold of his pen told him: “You are the centre of an astral conspiracy.”

“Our grossly material, earthbound lives are but shadows of our true being”

Genius, in other words, was a matter of destiny — and Pessoa’s destiny, he believed, was to win in death an immortal glory that would invert his obscurity in his own lifetime. When he was not yet 40, he wrote in a letter to a newspaper (typically left unfinished and unsent): “I feel younger every year because every year I am nearer to having never achieved anything in life… I have never made a real effort after anything, nor applied my attention strongly except to futile, unnecessary and fictional things.” For all his idler’s defiance, Pessoa was not untouched by the sadness of life unlived, of having done little with his existence other than daydream and scribble. In one of his reveries, Bernardo Soares, the heteronym that authored the scraps that make up The Book of Disquiet, recollects in one of his reveries the sense of mystery and wonderment he felt as a child on attending Mass. Soares confides to his diary an admission that, in light of Pessoa’s gnostic intimations of exile from divine origins, is doubly moving: “What I am would be unbearable if I couldn’t remember what I’ve been.”

Pessoa’s greatest outpouring of writings on esotericism occurred between 1931-1934, ending the year before he died. Acquaintances remarked on how, towards the end of his life, preoccupied with mortality, he gave off an otherworldly, mysterious, sage-like impression, as if he was only half here, half already in the beyond. Pessoa’s great Argentine contemporary, Jorge Luis Borges, admitted in old age that he found himself impatient with the mundane concerns of daytime, eager to get back to night with its far more serious business of dreaming. Pessoa — a writer who, had he not existed, Borges might have dreamed up — was likewise a man whose commitment to inaction, dreams, fantasy and the imagination went against the grain of modern life.

Ultimately, the Scottish poet and aphorist Don Paterson was not wrong, I think, when he remarked that the idea of reading Pessoa generally trumps the actual experience. The chief subjects of The Book of Disquiet, tedium and weariness (tédio and cansaço in the Portuguese language which, Pessoa once suggestively observed, has “no bones”), are hardly the most exciting or fertile of literary themes. Still, amid a culture frenzied with productivity and achievement, it’s refreshing to spend time in the company of so orientally inclined a writer, for whom “Action is a disease of thought.” Although Pessoa’s inner world was far richer than the abject Metaverse Mark Zuckerberg and his cohorts would have us live inside, aren’t we all, with our multiple online selves and our crowded-lonely worlds of techno-fantasy, living Pessoan lives now? His posthumous renown as Portugal’s great modern poet notwithstanding, it may be that Fernando Pessoa’s real achievement was only secondarily at the avant-garde of literature, and primarily at that of selfhood.

This news is republished from another source. You can check the original article here